Medical Emergency vs. Rad is the natural follow up to Fire vs. Rad because the responder priorities are exactly the same: Life, Property, and Environment. Though in some jurisdictions they swap the order of those last two.

Life saving efforts are always top priority though.

Which is why it is such a dick move at the level of war crime to drop/set off a second bomb 10-20min after the first to make sure you nail all the responders doing life saving efforts. But I digress.

But the Responder’s First Rule always applies: don’t become a victim yourself. If there is a chance for serious radiation exposure or material uptake by the responders, this matters and this is also why you have health physicists to tell you how long you can be in there. Acute external radiation exposure tends to not be an issue in these cases, but then there’s situations like the criticality accidents. Victims are most certainly dead if you don’t get them out immediately. The traditional advice of NEVER MOVE INJURED PEOPLE no longer applies.

First responders do have dose thresholds where we can ask them to do their jobs with higher than normal exposures, but we don’t ask them to jump into the heart of a reactor. No “biological robots” here. In the US, we have the following limits:

- .05Sv normal annual dose limit

- .1Sv work to save property

- .25Sv for life-saving/disaster mitigation

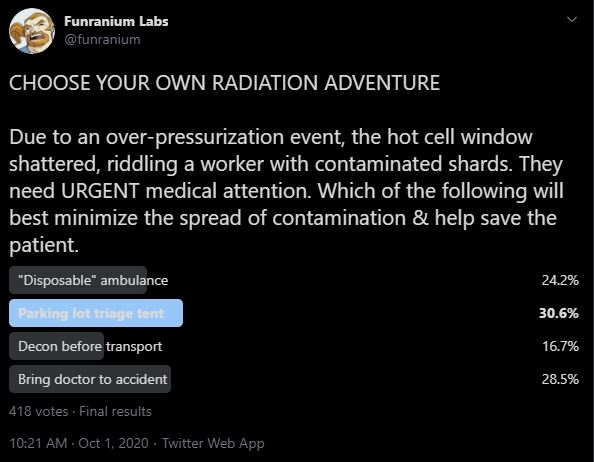

But in this scenario you have a living (for the moment), contaminated accident victim riddled with glass. The scenario asked you which choice would “best minimize the spread of contamination & help save the patient.” Because while life saving is a priority, we aren’t dumb. The less we have to move the victim, the less likely we are to injure them further AND the less likely we are to spread contamination. Potential contamination does matter, so someone responding to this accident also needs to be taking note of who has gone where. Probably several someones. Why does it matter? Because those are areas you’re going to have to go back and decon later after the medical part of the response is over. You have more time but man oh man is it easier when you have some notes about where to look.

The nice/horrible thing about the shards is that they constitute an internal uptake of radioactive material by injection. Your victim is politely containing that material in themselves and not spreading it as contamination for the time being. But since shards though clothes into the victim are gonna make the clothes hard to remove, you gently put them in Tyvek suit and load them off for transport to hopefully contaminate the ambulance as little as possible.

But if time is of the essence, you transport without delay. This is where you probably lose an ambulance for a while afterward. They’ve got impermeable surfaces and are meant to be cleaned because they transport malfunctioning meat colonies that may be very messy indeed. But, wow, there are so many nooks and crannies in those things. There is a point where you throw your hands up and write it off because the time & cost of labor to decon exceeds the cost of the ambulance itself. If you’re gonna be throwing an ambulance away, chose an old one. But sometimes you NEED that ambulance. During a mass casualty incident, contaminated victims can seriously wipe out your transport capability when you need it most. Plastic down that you replace every run, a quick meter survey for anything serious, and then you’re off again.

Which brings us to the hospital itself. In a perfect world, you’ve already got arrangements with the hospital for how to deal with contaminated patients, they’re trained for it, and you’ve all run drills together to make sure everyone knows what to do.

[waits patiently for the laughter to die down]

Hospitals do not appreciate SURPRISE CONTAMINATION INCIDENTS. Everything I said about ambulance decon applies to operating rooms too, though they’re more precious and difficult to clean. Before transport, you should call ahead to let them know what’s coming so they can prepare. They will open different doors, slap plastic up, whatever they can do to make a controlled, easily decontaminated corridor to an operating room with the least possible disruption to the rest of hospital operations. And, if they can, they will do this in the parking lot as triage. Might not be as sterile as an operating room, but any equipment & supplies they need for the triage tent are conveniently right in the hospital. Rad safety people from the worksite tend to come with the victim and they’ll get handed all the contaminated shards. Hospital doesn’t want ’em.

In the inspiring event for this scenario, the victim wasn’t working with a hot cell, though that certainly has happened in the past, but rather in a glovebox where the exhaust fan had a rather severe hiccup and causing the window to shatter. On a positive note, this means the victim didn’t get a face and torso full of shards but arms and hands instead. Through the gloves. Considering the actinides this glovebox was normally used for, that’s bad. It worth noting that the glovebox window going away immediately caused all the continuous air monitoring systems to go off, getting emergency responders headed that way immediately. Odds of a materials uptake by victim = VERY YES

GOOD NEWS: The gloves were thick enough that they caught most of the shards with only a few penetrating deeply.

BAD NEWS: The now exposed gloves were *very contaminated* from handling materials over the years and need to be kept from crapping everything up.

Yes, there is a specialized piece of radiation detection equipment called a Wound Counter.

Patient was conscious and making jokes through all this. Their favorite was “I don’t look forward to explaining my new track marks to the clearance investigator.”

The best part of it was that the punch biopsy they did just outright removed all the contamination in one wound. A bioassay which is actually decon is A+ work. The victim was scarred but fine, with quite the dose assigned to them over the next 40 years of their life.

~fin~